Shooting Film

reviews, history, and photos from 22 film cameras

Introduction

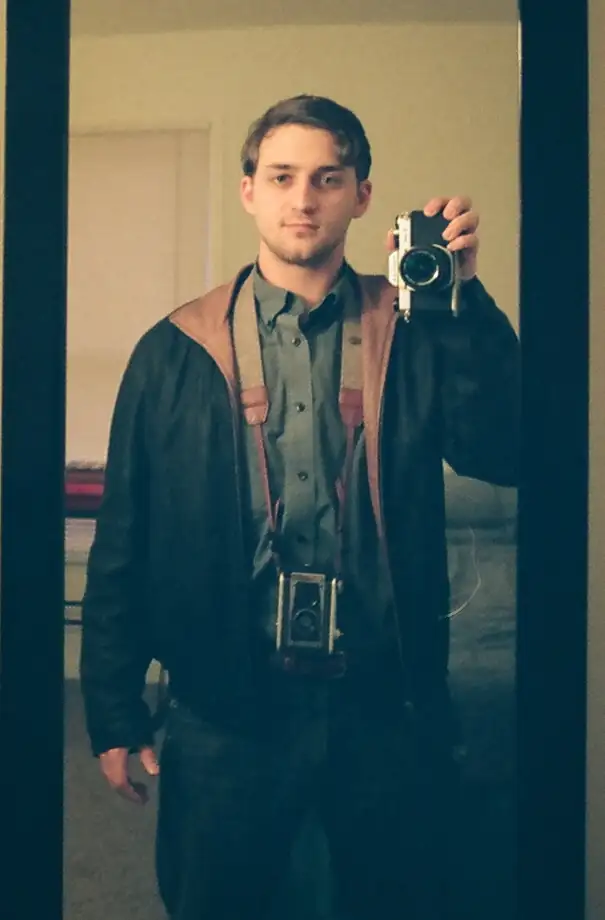

I have an unhealthy number of film cameras.

I used to think that I liked taking photos, but at this point, I think it’s time to accept that I just like hoarding the small metal boxes that take the photos. I have maybe 120 film cameras in total. Some that work, some that don’t, some I’ve taken photos with, and some that sit on shelves just lookin’ pretty. At some point, I’ll make a post that covers each and every one of them, but since that’ll take forever, this is the post you’re getting instead.

These are the cameras that I’ve actually shot film through. I’m not going to keep to a strict structure, but for each camera, I’ll try to give a brief overview, talk about the shooting experience, show some photos, and maybe give some comparisons.

There’s a table of contents if you want to jump to a specific camera, and you can also just click on the photos to view them full-size as a slideshow.

Table of Contents

- Nikon FM

- Nikon FM2

- Pentax K1000

- Yashica D

- Yashica 44

- Pentax 67

- Mamiya RZ67

- Balda Fixfocus 6x9

- Agfa Flexilette

- Kodak DualFlex

- Leica IIIa

- Nikon S2

- Nikon F

- Nikon F2

- Voigtländer Prominent

- Rollei 35 S

- Rapid Omega 200

- Hasselblad Xpan

- Fuji GW690ii

- Fujica GS645 Pro

- Zeiss Super Ikonta 531/2

Nikon FM

Overview

The Nikon FM was launched in 1977 as a fully mechanical 35mm SLR aimed at advanced amateurs. It was the lighter and more focused little brother of the professional Nikon F2, offering reliability, simplicity, and durability at a more affordable price. In an age when many cameras were beginning to rely on batteries to operate, it promised a reliable, fully mechanical operation that would never let you down.

My Camera

This was my very first film camera, and after a decade of shooting, it’s hard to imagine a better first choice. I bought it in 2016 from Malcolm and Betsy at Southerland’s Photo for about $150, and it came bundled with the minimalist pancake 50mm f/1.8 and a 55mm f/3.5 macro lens.

Over the next two years, I traveled extensively for work, and this camera came with me everywhere. It just simply works. It’s small, reliable, it takes great glass, and I love it.

Shooting Experience

My Nikon FM and FM2 are some of my absolute favorite cameras to shoot, and they are the benchmark by which I judge every other camera in my collection. These are extremely popular cameras, and there is an absolute avalanche of information on them on the internet, so here I’ll hit some of the highlights and less frequently mentioned features.

Light Meter

Although considered technologically advanced at the time, today not everyone loves the LED light meter, instead preferring the needle found in the early F models and in the FE. People claim it’s less accurate or that it doesn’t give you the same analog certainty as a needle. I certainly see the point here, but frankly, looking through several hundred photos I’ve taken with my FM, I struggle to find a single poor exposure. If you’ve ever heard this brought up as a negative point, I wouldn’t give it too much weight.

Viewfinder

For me, the viewfinder is one of the most important features of a camera. It’s literally the lens through which you see your future photograph—it’s how you focus and how you compose. It’s your connection to the photo.

In my view, the Nikon FM’s viewfinder is almost perfect—large and bright with a split prism, a microprism, and both aperture and shutter speed displayed. Like I’ve said about the camera itself, this is more or less the benchmark by which I judge other viewfinders.

I will say, I do slightly prefer the professional Nikon F2 viewfinder’s placement of the shutter and aperture. In the FM, the shutter is on the left, the aperture on the top, and the exposure on the right. This forces you to move your eye across the frame to read all the information. However, in the F2, they are all clustered neatly together at the bottom.

Lens Compatibility

Nikon’s core lens mount has remained the same since the introduction of the Nikon F in 1959. However, with the release of AI lenses in 1977, Nikon made a major change to the metering interface. AI lenses have additional material removed from the aperture ring along the rim of the lens which allows the camera to read the aperture setting.

This means that a pre-AI lens has “extra” material around the rim of the lens, which can prevent it from mounting on a camera with an AI metering prong.

However, unlike the later FM2, the FM has a folding aperture prong that can move out of the way and let you mount the oldest non-AI lenses. If you are looking for maximum Nikon lens compatibility, the FM is one of the best bodies to get.

That said, I have personally modified three or four non-AI lenses for AI compatibility, and it is pretty simple, so I wouldn’t let this be a deciding factor if you are looking at an FM2 or FE2 instead.

Pancake Lenses

The Series E pancake lenses were a cheaper and smaller alternative to the faster and more expensive Nikkor lenses. I own plenty of both varieties, and it is true that the Series E lenses are cheaper and have more plastic. However, there are several versions of the Series E. Notoriously, there is a cheap and underperforming full-plastic one.

Avoid the full-plastic one if you can. Instead, get what I have, which has a chrome ring and is actually quite good. Despite the naysayers, they have a bit of a cult following because of how small, portable, and cheap they are. If there is one downside, it is that the 50/1.8 E has a minimum focusing distance of 0.6m, compared to 0.45m for the 50/1.4 AIS.

Shutter Lock

All the Nikons have a shutter lock that is integrated with the film advance. You slightly cock the film advance to turn on the light meter and unlock the shutter button. Newcomers to the camera often struggle with this, but it is, in my opinion, a very elegant solution that is easy and natural to use once you start shooting. Essentially, you just always advance the film anyway after taking a shot—it feels seamless to prepare the lever ahead of time. This functionality also saves battery and prevents accidental exposures, and it’s a feature I’ve found myself missing on other bodies.

Tech Specs

- Dates Manufactured: 1977–1982

- Camera Type: SLR

- Format: 35mm

- Primary Lens: 50mm f/1.8 Series E Chrome Ring (3291471, from 1981–1985)

- Minimum Focusing Distance: 0.6m

- Shutter Speeds: 1s to 1/1000s, B

- Light Meter: 60/40 center-weighted, CdS (cadmium sulfide)

- Country of Origin: Japan

- Weight w/ Lens: 729g

- Serial Number: FM 3091999

Nikon FM Photo Samples

Nikon FM2

Nikon FM2 Overview

The Nikon FM2 is arguably one of the best manual film SLRs ever made. Introduced in 1982 and produced through various revisions until 2001, this camera was originally marketed to advanced amateur and semi-professional photographers who demanded absolute reliability and rugged performance.

Debuting with a body-only price of around $364 (chrome version) and later climbing to around $745, it was built for those who wanted a fully mechanical tool—operable without batteries (except for its light meter). Praised for its fast vertical-travel shutter (capable of 1/4000 sec) and precise, minimalist design, the FM2 quickly earned a reputation as a “tank” that could shoot in the most extreme conditions. Notably, its robustness and simplicity even won over legendary photojournalists. If you’ve ever seen the iconic “Afghan Girl” portrait, that was taken with an FM2.

My Camera

I purchased my Nikon FM2 right around the time I stopped traveling for work and shifted to medium format photography. Although that means I don’t have as many shots from my FM2 as from the FM, this is undeniably my desert island camera. With a fully mechanical design, a 50/1.4, and a top shutter speed of 1/4000s, it’s very hard to argue with its raw capabilities. It honestly makes it hard to convince myself to shoot with any of my more exotic cameras. It’s everything that I love about my FM, but with slightly better technical specs.

I really cannot stress how OP this camera is. I’ve got a Leica IIIa, Fujica 645, Pentax 67, Voigtländer Prominent, Yashica D, Rollei 35, Zeiss Ikonta, Exakta VX… just so many cool cameras, and yet sometimes it just hurts my soul to shoot them.

I’ll go to take a shot with my gorgeous Voigtländer, wide open at 1.5, only to be thwarted by the 1/500s shutter speed. Or I’ll be out and about with my compact Fujica 645 and its gorgeously huge negatives, only to realize that I can’t focus any closer than 1m, and I have to rethink my shot. Or I’ll be reveling in the crystal-clear view of the world through my Pentax 67’s massive chimney viewfinder, only to be forced to take my eyes away every time I want to adjust the aperture or the shutter speed.

Simply put, the FM2 is a camera that makes everything about shooting film easier, and you can’t help but be reminded of it anytime you handle an inferior user interface.

I have 120+ film cameras, in large part because I love cool and unique mechanical objects. In my heart of hearts, I desperately want to be that guy with the crazy camera you stop and chat with on the street. But god help me if the FM2 doesn’t make it hard to shoot anything else.

Tech Specs

Like the FM, there’s a ton of information about this camera already on the internet. Instead of regurgitating it, here’s a fantastic comparison between all of the FM and FM2 features.

However, just in case you haven’t already heard, this camera has a freaking titanium honeycomb shutter, just so it can shoot at the insane 1/4000th of a second!

- Dates Manufactured: 1982-2001

- My Date: 87-89 (need to confirm after I finish the current roll of film)

- Type: SLR

- Format: 35mm

- Primary Lens: Nikkor 50mm/1.4 AIS, 1981-2005, 5220802, ~1985

- Minimum Focusing Distance: 0.45m

- Shutter Speeds: 1s to 1/4000s, B

- Light Meter: 60/40 center-weighted, SPD (silicon photodiodes)

- Country of Origin: Japan

- Weight w/ Lens: 799g

- Serial Number: N 7612622

Nikon FM2 Photo Samples

Pentax K1000

Overview

The Pentax K1000 is commonly cited as being the most popular student photography camera to ever exist. It was manufactured for over 20 years, from 1976 to 1997, and it is estimated that over 3 million were made. With its rugged metal construction, simple controls, and built-in light meter, it is easy to see the appeal. The camera was typically bundled with a 50/2 lens, but the K mount offers plenty of nicer glass to choose from, including a 50/1.4, an 85/1.7, and a 135/2.8.

It’s simple, it’s reliable, and it’s cheap. It takes perfectly good photos, and if you can pick one up for a budget price, you will not be disappointed.

Shooting Experience

However, if you are looking for the best 35mm SLR shooting experience, this is not it. In my estimation, it is inferior to my Nikons in almost every detail. The lens release button feels cheap and fragile, the max shutter speed is only 1/1000th, it lacks a shutter lock, there is no self-timer, no aperture preview, no viewfinder display of aperture or shutter speed, and the shutter speed dial is significantly less easy to adjust. While my FMs have both a split prism and a microprism, the K1000 only has a microprism, and in general, the viewfinder feels dimmer and worse.

To its credit, some people prefer the Pentax’s needle light meter to the Nikon FM and FM2 LEDs. However, the Pentax light meter is always on, unlike the Nikon, which is turned off via the film advance lever. You can trick the Pentax light meter into not using as much electricity by using a lens cap, but I still find that my Pentax batteries are always dead, while my Nikons last years.

I’ve only shot one roll through my K1000, and that was enough for me.

Miscellany

Supposedly, if your Pentaprism says AHCO, as mine does, then it was made in Japan, not Hong Kong. However, mine has a sticker on the bottom that clearly says “ASSEMBLED IN HONG KONG.” Actually, while trying to track down my 50/2, which I’m sure I own for this camera, I discovered that I actually own TWO Pentax K1000s. My second must be a newer model, as it only says Pentax on the prism.

Tech Specs

- Dates Manufactured: 1976–1997

- My Date: 1982–1983

- Type: SLR

- Format: 35mm

- Primary Lens: SMC Pentax-M 28mm f/3.5, 6873910

- Minimum Focusing Distance: ??

- Shutter Speeds: 1s–1/1000, B

- Light Meter: 60/40 center-weighted, CdS (cadmium sulfide)

- Country of Origin: Japan

- Weight w/ Lens: 785g

- Serial Number: 7093688

Pentax K1000 Photo Samples

Jan 2017, Fujicolor Superia xtra400, Huntsville, Al

Jan 2017, Fujicolor Superia xtra400, Huntsville, Al

Yashica D

Yashica D Overview

When walking on the street with this camera, you will often get stopped by strangers who want to know, “Is that a Rollei!?” Sadly, no, it is not. After World War II, the German camera industry was in shambles, with many of the major factories either bombed out or stripped of their equipment by the Soviet Union. Meanwhile, the Japanese economy was being supported by the United States, and Japanese camera companies began to rise to prominence.

The now-famous names of Canon and Nikon were just getting their start, and many of their first cameras were not original designs but instead direct copies of well-respected German cameras from the 1930s. Yashica was no different, and the Yashica D is a none-too-subtle copy of the premium German Rolleiflex.

Produced by Yashica from 1958 to 1972, the Yashica D stood as the company’s top knob-wind twin-lens reflex (TLR) model. It originally sold for around $50, a 2025 price of $530.

From 1970–1972, the original three-element Yashikor triplet lenses were replaced with the four-element Tessar-design Yashinon lenses, with the viewing lens increasing from f/3.5 to f/2.8. Paul Sokk has an excellent and wonderfully obsessive site where he details every possible thing you could want to know about the Yashica lineup.

Personal Story

In January of 2017, I got it in my head that I needed to start shooting medium format for the image quality, and a quick perusal of eBay revealed that TLRs were the sexiest cameras I had ever laid eyes on. They were like some steampunk fantasy that actually took great photos.

Now, obviously, if you want a TLR, the first thing that comes to mind is a Rolleiflex, but seeing as I don’t have a money tree in my backyard, my sights fell on Yashica. Yashica sells a lot of models—the A, B, C, D, 124G, etc.—with the D being the best fully mechanical version made. It comes with two lens options, the 3.5/3.5 Yashikor or the 2.8/3.5 Yashinon, which has a brighter viewing lens and improved taking optics. I didn’t know this at the time, but apparently, the Yashinon lenses were only made on the D between 1970 and 1972, making my model a bit of a rarity.

So anyway, in my quest to acquire a high-performance, medium format workhorse, I located a wildly expensive $276 Yashica D, complete with a recent CLA and a freaking six-month warranty, which is insane for a 45-year-old camera.

To give you an idea of the kind of quality I was expecting when I purchased it, I set up an oscilloscope and a light sensor to measure the shutter speeds. If I remember correctly, 1/500s is actually a little slow, but everything else was spot on.

Shooting Experience

The Yashica is a very charming camera to shoot with. It’s often touted for its bright viewing screen (especially the f/2.8 model), and I find that this is absolutely the case. The waist-level viewfinder with the pop-up magnifier is a joy to use and makes focusing a breeze. The camera gets quite a bit of attention on the street, and when you hand it to strangers, they are inevitably taken aback by the viewing experience.

The controls are also quite nice. Symmetrically oriented on the front of the camera, you rotate the aperture and shutter dials with the thumb and index finger of your left hand, watching their progress in the perfectly positioned viewing window situated on top of the viewing lens. Meanwhile, the right hand adjusts the focus, shutter, and film advance. If there is a downside, it is that careless procedure can lead to double exposures, which has ruined a few of my otherwise favorite shots.

It’s unavoidable that it be compared with some of my other medium format cameras, and set against something like the Pentax 67 system (with its faster lenses and better shutter speeds), the Yashica D lags in sheer performance. An 80mm f/3.5 with a shutter speed range of 1s to 1/500s is not exactly going to give you the creative freedom of the Pentax. I’ve done some comparison shoots between it and the Pentax 105/2.4, and there is really no comparison between their capabilities.

Yet for me, there’s an undeniable charm to the TLR experience, and it’s just such a delightful camera to carry around. Petty though it may be, it has a passerby wow factor that is almost unmatched in my camera collection. Honestly, writing this has reminded me just how enjoyable it is to use, and I’m already itching to take it out for another spin.

Miscellany

Interestingly, my particular example has “9-28-78” penciled inside, likely a service date.

Specs

- Dates Manufactured: 1958–1972

- My Date: 1970–1972 (based on Yashinon viewing lens)

- Camera Type: TLR

- Format: 120, 6×6

- Lenses:

- Viewing Lens: Yashinon 80mm f/2.8

- Taking Lens: Yashinon 80mm f/3.5

- Minimum Focusing Distance: 1m

- Shutter Speeds: 1s–1/500s + Bulb

- Country of Origin: Japan

- Weight: 946g

- Serial Number: D 7122389

Yashica D Photo Samples

Yashica 44

How to Shoot with 35mm

Camera Modifications

I found that many instructions online for converting this camera to shoot with 35mm were rather simplistic. Suggesting that you could just throw in a 35mm roll and that would be it. However, at least on my copy, I found that the 127 film cradles were overly stressed by the 35mm cartridge, and that removing them completely gave a better fit. Additionally, I found that the film pressure plate would hit the edge of the 35mm cartridge, potentially damaging the plate and definitely not providing any tension on the film.

I ended up printing a new plate from Xlucine, and it has worked quite well so far.

Frame Spacing

My Yashica is the winding lever variant, and I ran a roll through it while marking with sharpie to check the frame spacing.

- shoot the first 5 shots without reseting, cranking TWO TIMES for each shot

- take all remaining shots by reseting and winding once

Just to be abundantly clear about this process:

- reads 1, shoot first shot

- wind twice

- reads 3, shoot second shot

- wind twice

- reads 5, shoot third shot

- wind twice

- reads 7, shoot fourth shot

- wind twice

- reads 9, shoot fifth shot

- reset, wind once

- reads 2 take sixth shot

- reset, wind once

- reads 2 take seventh shot

Yashica Sample Photos

fun shot I took before getting the frame spacing figured out – you can see the overlaping frames on top and bottom, but I think it gives it a vibe

Pentax 67

Although the famous 105mm f/2.4 with the wooden pistol grip is the most iconic loadout for this camera, I actually typically use it with a chimney finder, the wonderful 45mm f/4.0, and a custom burl wood grip.

Pentax 67 Overview

Produced between 1969 and 2009, the Pentax 6x7 is one of the most iconic medium format systems in existence. With a 6x7 cm frame size, it offers negatives almost 4.5 times larger than 35mm film but in a familiar SLR form factor. Originally costing two to three times more than its 35mm counterparts, the 6x7 was aimed at professionals and serious enthusiasts who wanted the high-resolution benefits of medium format without abandoning the familiar SLR handling. It was famous for its use in high fashion and editorial photography, and it maintains a cult following into the digital age.

There are four versions to be aware of. The original 1969 6x7 was made for about a decade until, in 1976, the addition of mirror lockup attempted to address the prodigious mirror slap, along with improvements to the film advance system. In 1990, it was rebranded as the Pentax 67, with improvements to metering and shutter timing; and finally, the Pentax 67II arrived in 1999 with a major overhaul and a more plasticky body.

If you are going to buy one, the 6x7 MLU and the 67 represent the best balance of price and quality. The original 6x7 has a less reliable film advance and should be avoided if possible, while the 67II is significantly more expensive and potentially harder to repair.

Personal Story

I first encountered the Pentax 67 at Central Camera in Chicago, and it took my breath away. After years of shooting a 35mm Nikon, seeing the Pentax was like realizing you could have a pet bear instead of a poodle. Although I’m usually very tentative about my purchases, I was on the verge of impulse-buying it on the spot when the clerk demanded to know if I was there to buy or simply to ogle. Needless to say, I did not buy it. I went straight home and bought one on eBay instead, and since then, I’ve dropped a shameful amount of my disposable income on the body, lenses, and various accessories.

Accessories

Overview

Like I said, I own a gratuitous number of accessories for this system. I’m going to list them here to give a general idea of what’s available and to digitally flagellate myself for spending so much money. If I had realized how much accessories cost separately, I would have waited for a camera that included them.

Interestingly, I have the nice, SMC 67 version for all the lenses except the famous 105.

| Accessory | Price | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Body | $297 | …Seemed cheap at the time |

| Burl Wood Right Hand Grip | $139 | Best investment you can make |

| Factory Left Hand Grip | $130 | Useless but pretty |

| Extension Tubes | $79 | Excellent for improving the minimum focus distance |

| Chimney Finder | $50 | Incredible magnification, but no light meter |

| TTL Prism Finder | $149 | Never use it |

| Strap Lugs | $50 | I mean, you have to have them… but damn |

| Quick Focus Ring A | $45 | Sigh |

| 45mm f/4 | $258 | My favorite lens, incredible detail |

| 105mm f/2.4 | $200 | The famous lens, but not as good as people say |

| 165mm f/2.8 | $230 | Excellent portrait lens |

| 200mm f/4 | $110 | It’s okay? I never use it |

Handles

More than any other feature, people recognize the Pentax 67 by its ostentatious wooden handle. It gets tons of comments when walking around town, and it is touted online as the perfect way to hold this boat anchor of a camera.

But functionally? The handle is a monumental failure of human design. The engineers who first proposed this handle should be committed to an institution to protect the public from their ideas. I can’t believe this isn’t more talked about because, seriously, the thing is useless.

It’s in exactly the wrong place for you to hold while shooting since your right hand needs to adjust the aperture and focus. And yes, I do own the gimmicky Quick Focus Ring A, which is a giant pain in the ass—inventing a solution for a problem that shouldn’t exist.

If you own this camera, do yourself a favor and skip the factory grip, and instead buy a right-hand grip. Mine is burl wood shipped to me from the charmingly named “Village no. 1” in Bangkok, but these days, I think the place to shop is Pimp my Pentax on Instagram.

Viewfinders

There are at least four viewfinders for this camera: a standard prism, a TTL prism, a waist-level, and the chimney finder. I own a TTL and a chimney finder, and I adore the chimney. It provides the largest, most magnified, most beautiful viewfinder of any camera I own. Sadly, my particular Pentax has the fully matte focusing screen instead of the standard split prism, but the chimney finder is so gigantically magnified that it makes precision focusing a breeze.

I would love to eventually pick up the waist-level finder, but they are a heart-stopping $250 from Japan, and I haven’t yet been able to stomach the expense.

If you are going to use the TTL finder, I have a 3D-printed ribbed sleeve that I made for the shutter speed dial. It makes it much easier to adjust the shutter speed.

The Mythical 105mm f/2.4

People buy the Pentax 67 just to use this one single lens. It has an unbelievable cult status in the world of film photography, famous for its insane depth of field, beautiful rendering, and “3D pop.” Seriously, people online will rave endlessly about this lens, positively frothing while they declare that the look is impossible to achieve on 35mm. They will say that medium format has more bokeh than 35mm or that the 105mm will be more compressed than the 50mm, giving better background separation.

And it is a nice lens.

But frankly, it is no different from a common 50mm f/1.2 on 35mm. There is absolutely nothing magical about it, and there is certainly no mystical 3D pop due to the lens itself. Essentially, the 105mm f/2.4 on a 6x7 negative is roughly equivalent to a 50mm f/1.2 on a 35mm negative in terms of both framing and depth of field.

But doesn’t the 105 have more compression than the 50? Sadly, no. Compression is not caused by the length of the lens; it is a function of the distance between the film plane and the subject. Since the 105 and the 50 have the same framing on their respective systems, the subject distance and therefore compression will be the same.

Yes, I know. I’m a dirty, Pentax-hating apostate for even suggesting it. But seriously, check out this comparison video by Julien Jarry if you don’t believe me.

It also has a miserable minimum focusing distance of 1m, making it a pain to compose close artistic shots. It’s bad enough that I’ve taken to carrying around an extension tube just to be able to focus on my subjects.

Why Bother?

So if the famous lenses aren’t really any better, then why bother with an expensive, heavy, massive camera that only gets 10 photos per roll?

Well for starters, the negatives are gigantic. On top of having way more detail and less grain, I find them easier to develop and easier to scan. Only 10 photos per roll certainly seems like a downside, but as a slow and deliberate shooter, I rather appreciate not struggling to take 36 photos on a 35mm roll. While looking through my cameras for this post, I discovered that I have 10 shots still left on my Pentax K1000 that have apparently been in the camera for EIGHT YEARS. This is not a problem you run into on the Pentax 67.

If I want to shoot a detailed landscape shot, there isn’t a better camera in my collection than the Pentax 67 with the 45mm lens. The resolution and detail are just insane.

Shooting Experience

If I’m heading out specifically to shoot photos, the Pentax 67 is at the top of my list. The massive negatives, the awesome lenses, the undeniable conversation factor—it’s just so much fun.

However, if I’m out and about and want a camera “just in case,” the Pentax 67 stays at home. I could walk around with literally three Nikon FM2s hanging from my neck, and they would take up less space than the Pentax. Carrying this thing slung over your shoulder for a day is enough to give you adult-onset scoliosis.

It also simply has limitations that my more fully featured 35mm systems do not. Looking through my various Pentax photographs, I notice quite a few where I had to compromise on the exposure. It’s not the biggest deal in the world, but a max shutter speed of 1/1000 and a max aperture of f/2.4 mean that unless you are also lugging around tripods and ND filters, you will be hard-pressed to shoot wide open in the day, and you will struggle to keep shooting as the sun goes down. A tip I would give for low-light shooting is to engage the mirror lock-up and let yourself shoot a stop slower than you think you can.

Finally, it really, really bears mentioning that the minimum focusing distance on almost all the lenses is miserable. Even if you get the 90/2.8 instead of the 105, the minimum focusing distance is still 0.65m, admittedly a huge improvement over the 105’s 1m but still a far cry from the 0.45m of my Nikon 50/1.4.

| Pentax | Nikon | |

|---|---|---|

| Wide | 45/4 (0.37m) | 24/2.8 (0.30m) |

| Normal | 105/2.4 (1.0m) | 50/1.4 (0.45m) |

| Portrait | 165/2.8 (1.6m) | 85/1.8 (0.85m) |

| Long | 200/4 (1.5m) | 105/2.8 (0.314m) |

In all, the Pentax 67 is a fun camera, and I love it. But unless you specifically want high-resolution, huge negatives—like for epic landscapes or studio portraits—you might really consider taking a smaller and more fully featured camera.

Tech Specs

- Dates Manufactured:1990-1999

- Camera Type: SLR

- Format: 120, 6x7

- Primary Lens: 150/2.4 5434074 or 45/4

- Minimum Focusing Distance: 1m

- Shutter Speeds: 1s - 1/1000s, B

- Light Meter: TTL, or None

- Country of Origin: Japan

- Weight w/ Lens: heavy as fuck

- 2040g, (chimney, right grip only, 45/4)

- 2556g, (TTL, right grip only, 104/2.4)

- Serial Number: 4174966

Even with inexpensive, medium quality scans, the resolution and detail in the Pentax is insane. Look at this zoomed in crop of the above photo, where you can see two tiny people in the distance. This particular shot was taken with the SCM Pentax 67 1:4 45mm lens, which is the sharpest and most optically advanced of the three 45mm lenses available for the Pentax 67.

If you want to take gorgeous landscape shots and worry about cropping later, it’s hard to beat a Pentax 67 with a 45mm lens.

Pentax 67 Photo Samples

.webp) the wide 45mm lets you do nice long crops

the wide 45mm lets you do nice long crops

Mamiya RZ67

Mamiya RZ67 Example Photos

Balda Fixfocus 6x9

Overview

I have a lot of 1900s–1930s folder cameras floating around the house, very few of which I have actually bothered to run film through. A big problem is that many of them take weird film formats that were discontinued decades ago. Just take a look at this table of formats:

| Format | Introduced | Image Size | Availabilit | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roll Film | ||||

| 120 | 1901 | 6×4.5, 6×6, 6×9 cm | Available | Dominant medium format today |

| 620 | 1931 | 6×4.5, 6×6, 6×9 cm | Discontinued | 120, but with a smaller spool |

| 127 | 1912 | 4×6.5 cm | Limited availability | Still produced by niche manufacturers |

| 116 | 1899 | 6.5×11 cm | Discontinued | Scarce; requires DIY solutions |

| 616 | 1932 | 6.5×11 cm | Discontinued | 116, but with a smaller spool |

| 122 | 1903 | 9×14 cm | Discontinued | Large negatives; difficult to source |

| 135 (35mm) | 1934 | 24×36 mm | Widely available | Dominant film format today |

| Sheet Film | ||||

| 2¼×3¼” (6×9 cm) | Early 1900s | 2¼×3¼ inches | Available | Commonly used small sheet film, especially in press cameras and small folders. |

| 3¼×4¼” | Early 1900s | 3¼×4¼ inches | Limited availability | Less common today but historically widely used in folding press cameras. |

This particular camera is unbranded, but the film viewing window cover bears the marks “DRGM” and “BW.” This leads me to identify it as a Balda 6x9 of an unknown model, probably a Fixfocus, produced between 1933 and 1938.

I came across a few nice resources while researching it, including this page on the Fixfocus specifically, a lovely interactive timeline of the Balda Camera models, and an in-depth review of a newer iteration of my camera.

Shooting Experience

I took two of my 6x9 folders on a trip to Nevada in 2017, and I’m pretty sure these are the photos from the Balda. They’ve got an interesting lo-fi look, which I believe is caused by light leaks from the body, possibly through the film viewing holes. The bellows on this camera don’t have any pinholes, so I don’t think they are to blame.

Shooting this camera is a bit of a pain. It has no light meter, no way to see if the subject is in focus, no shutter release on the body, no double exposure interlock, a maximum aperture of only f/4.5, and a max shutter speed of only 1/125th. For all that, though, the rotating viewing window is actually very bright and clean—a rarity in these old cameras, as they are typically dim and hard to see through, often with mirror issues.

The shutter cocking is also really nice. The cocking lever moves from left to right, and as soon as it is cocked, your thumb naturally lands over the shutter release, which you can press immediately to fire the camera. On many of my leaf shutter cameras, the cocking lever is in some unintuitive place that you have to hunt for, and then the shutter release is in some other random location. Not so with the Balda—your fingers just naturally land in the perfect place.

This is not the sort of camera I would take out a second time, but I had fun running a roll through it.

Tech Specs

- Dates Manufactured: 1933-1938

- Camera Type: Folder

- Format: 120, 6x9 or 6x4.5 with mask

- Lens: Schneider-Krieuznoach Radionar 10.5 cm f/4.5

- Minimum Focusing Distance:

- Light Meter: lol

- Shutter Prontor

- Shutter Speeds: 1/25 - 1/125, with T and Bulb

- Country of Origin: Germany

- Weight: 590g

- Serial Number: None

Balda Fixfocus 6x9 Photo Samples

Pay attention to the wide shot of the river, as I took the same photo with the lovely Agfa Flexilette below.

Agfa Flexilette

Overview

Made for only one year in 1960, the Agfa Flexilette is one of a select few 35mm TLRs ever produced. Commercially, it’s considered a bit of a flop, and it was replaced a year later with the Optima Reflex. It was a somewhat expensive camera, with Mike Eckman estimating that it would have sold for $106 in 1960 (about $1,150 in 2025). I bought mine in Huntsville, AL, at Firehouse Antiques for around $50, in shockingly mint condition. Interestingly, Mike mentions that he cannot find any instances of the camera being sold in the U.S., so I can only assume that mine made its way to Huntsville via the German engineers who moved here after the war.

In case the pictures don’t make it obvious, it’s a TLR, where the bottom lens is used to take the photo and the top lens is used to compose the shot. It’s a weird mix of obviously well-thought-out engineering and uncomfortable ergonomics. The film advance lever is gorgeously machined into the perfect shape for your thumb, with just the right amount of knurling. It’s not a piece of flat stock that has been bent; it looks machined from a solid piece of metal. It would not be an exaggeration to call it one of the most premium advance levers in my entire collection—I’m frankly shocked they chose to manufacture it this way.

Meanwhile, the focus and aperture controls are… questionable at best. Yes, they’ve done an excellent job packing all the controls into a thin pancake lens, but at the cost of them actually being big enough to comfortably use with your soft human fingers. The focus ring is knurled, scalloped, and only 2.25mm thick, and it is a literal pain to use. Perhaps in the 65 years since its manufacture, the lens grease has stiffened, but reading online, this is an almost universal complaint.

The aperture ring is a bit better, but only because it moves more smoothly. It has the flaw of being too close to the body, presenting its own difficulties. Charmingly, the shutter speed, which is flush with the body and should by rights be the hardest to adjust, is actually the easiest. They’ve added two large finger grips, making it a breeze to turn.

To be fair, other contemporary cameras, such as the Zeiss Contaflex, are also a pain to operate, but I wouldn’t say this shared complaint excuses either manufacturer.

In stark contrast to its controls, the viewfinder is absolutely top-notch. It deploys by the aid of a small knob on the back, which sadly fell off my camera during my ownership. The deployment is firm and confident, putting it in waist-level finder mode. By flipping up the magnifier, you can do precision focusing or use the excellent sport finder. The sport finder really deserves praise for its lenses, which—quite unlike any other sport finder in my collection—elevate it over the normal hollow metal frame. The viewfinder is bright and crisp, with a split prism in the center that makes focusing trivially easy. The scene you see through the magnifier is massive. Compared to my Nikon FM2, I think it might take up as much as 4x the physical area in my eye’s field of view.

Mike Eckman has a great write-up on the camera that goes into more detail than I have here. He talks a lot about its general place in history and the state of the German camera market.

It’s a sort of weirdly positioned camera, with a premium build and an intermediate price, and it’s not clear to me who the market was. Despite the finicky controls, the unique design and the excellent viewfinder make it a delightful little camera to shoot with, and I should honestly take it out more.

Miscellany

Inside, mine has a little advertisement for Agfa Isopan Agfacolor IF 17, Pat 36.

Tech Specs

- Dates Manufactured: 1960

- Camera Type: TLR

- Format: 35mm

- Primary Lens:

- Design: 3 element

- Specs: AGFA Color Apotar 45mm f/2.8

- Min Distance: 0.9m

- Shutter:

- Speeds: 1 - 1/500, B

- Type: Leaf

- Light Meter: None

- Country of Origin: Germany

- Weight w/ Lens:

- Serial Number: AC 3584

- Manual: here

Agfa Flexilette Photo Samples

Kodak DualFlex

The Kodak Duaflex IV is an unabashedly budget camera made from 1955 to 1960. It was marketed directly to families for taking snapshots of vacations, important moments, and everyday life. With its bright TLR viewfinder, it was meant to be an upgrade over simple box cameras like the Brownie while still being insanely affordable. The bodies are made mostly of Bakelite with some metal features, and the lenses are incredibly simple meniscus designs. They have no focusing, a fixed aperture of around f/15, and a single fixed shutter speed of about 1/30 of a second.

It’s really hard to get simpler than this camera. They were priced at $14.95 in 1960, which would be about $160 in 2025. Mine is pictured with the optional flash unit, which would have brought the total cost up to $19.95. Jeremy Mudd’s post shows a lot of great ads for these cameras, and it’s worth checking out.

Despite looking superficially like Yashicas or Rolleiflexes, these cameras do not take 120 film. Instead, they use 620, which was probably a choice by Kodak to lock users into their own film sales. 620 is the same physical film as 120, but it is wound on a smaller spool, which means that if you want to shoot these cameras today, you need to unwind your 120 film and then rewind it onto a 620 spool. This is an endeavor I have only bothered to do once—and one I am unlikely to repeat.

It’s pretty typical for these to come with dirty viewfinders and internal mirrors, and it’s a very easy fix. I think this was the second or third film camera I ever shot, and it was the first that I ever “repaired.”

The actual shooting experience is pretty minimal: aim the camera, press the shutter, wind the film. You do need to plan your film and lighting carefully, as the fixed aperture and shutter speed mean you are at the mercy of the film’s latitude and the sun’s whims.

Tech Specs

- Dates Manufactured: 1955-1960

- Camera Type: TLR

- Format: 620, 2¼ x 2¼ ?

- Primary Lens: Kodet

- Minimum Focusing Distance: ~5ft

- Shutter Speeds: Instant, Long

- Light Meter: None

- Country of Origin: ‘Murica

- Weight w/ Lens: 462

- Serial Number: None

Kodak DualFlex Photo Samples

Leica IIIa

Overview

The original Leica was a groundbreaking camera. You can read about a million articles on its importance, so I don’t want to rehash everything here. But to summarize, Leica defined the entire photographic industry for 100 years, transforming it from a world of large, medium format bellows cameras to the small, 35mm cameras that we all know and love today.

The Leica I was released in 1925, with a fixed lens and no rangefinder. Over the next decade, various improvements were made until we get to what I have here: the Leica IIIa, which has most of the modern features we expect from a camera—minus a light meter.

My particular Leica was made in 1937, and the model line continued to receive various updates, such as improvements to the viewfinder and the addition of flash sync, until it was eventually superseded by the M series in the 1950s.

My Camera

I came across mine hidden in the back of an antique shop outside of Las Vegas for $175, and I bought it without a second thought. At the time, I didn’t know the difference between the Leica M series and the Leica III, and I was very worried that at that price, I may have accidentally bought a fake.

There are, in fact, a shocking number of fake Leica IIIs floating around in the world. This is one of the most directly copied cameras ever made, with almost exact clones produced by many contemporary manufacturers up through the 1950s. Specifically, many Russian clones have been rebadged and sold as Leicas, so if you’re ever searching for one on eBay, you’ll want to be careful.

But why all the copies?

Well, I think the Leica III may have been one of, if not the, best 35mm camera in existence when it was made in 1937. It has a magnified and accurate rangefinder, a 1/1000 shutter speed, an f/2.0 lens as standard (with f/1.5 available), and it was built like an absolute tank. I have a lot of cameras, but when I want to impress a visitor with the mechanical beauty of a camera, I always show them my Leica.

Shooting Experience

When I bought my camera, it had some obvious haze on several internal elements, which gave the photos a dreamy, low-contrast feel. As I mention later in the Zeiss Ikonta section, removing haze on old lenses is typically quick and easy, so after owning it for a few years, I did just that.

With all the benefit of hindsight, I now regret cleaning the haze. Frankly, I have piles of cameras that can take sharp, contrasty photos, but the dreamy, low-contrast look of the hazy lens was something unique and special.

To actually shoot the camera, you famously have to cut the film leader and carefully insert it in the back. The internet is divided on how much of a trial this truly represents, but I personally have never had an issue with it.

The rangefinder also has some quirks. Any user of a rangefinder made in the last 75 years will expect that the viewfinder used to see the subject is the same one that contains the rangefinder patch for focusing.

Not so with the Leica. Instead, there are two windows: a wide viewfinder and a magnified rangefinder window. Although later cameras combined the two as a feature, I actually quite like the separated finders. The magnified rangefinder patch is wonderful and makes nailing critical focus a breeze.

For the sake of comparison, in addition to my 1937 Leica, I also have a 1937 Zeiss Super Ikonta 531/2. It also has a zoomed-in rangefinder, though not quite as magnified as the Leica’s.

The focusing on the Leica is excellent. There’s a rock-solid knob that locks the focus at infinity, and you can grip it with your thumb while focusing. It feels excellent, and combined with the magnified viewfinder, makes focusing a breeze. The film advance is similarly premium, with a large, knurled knob that feels excellent in the hand.

Overall, shooting the camera feels surprisingly modern, and carrying around such an engineering marvel is a joy.

Miscellany

Interestingly, Leica as a company appears to have been very consumer-friendly; you could send your Leica back to the factory for upgrades instead of buying a new camera. For instance, my relatively early IIIa, made in 1937, has no flash sync. It wasn’t until 1951 with the IIIf that Leica introduced flash sync. When I found this out, I was greatly confused because my particular Leica has a seamlessly installed flash sync on the back, right underneath the shoe mount.

Apparently, it was common for both the Leica factory and third-party shops to retrofit Leica cameras with flash sync and other features.

Tech Specs

- Dates Manufactured: 1935-193?

- My Date: 1937, how to date

- Camera Type: Rangefinder

- Format: 35mm

- Primary Lens: Summar 5cm 1:2, 334922

- Minimum Focusing Distance: 1m

- Shutter Speeds: 1s - 1/1000, B, T

- Light Meter: No

- Country of Origin: Germany

- Weight

- Body:

- w/ lens:

- Serial Number: 261451

Leica IIIa Photo Samples

Nikon S2

Nikon S2 Photo Samples

Nikon F

Seen here pictured with 3 different finders.

Nikon F Photo Samples

All these photos are taken with a new film stock I’m trying, LomoChrome Metropolis. I’ve been looking around for a color film that just oozes that film look, and this is a pretty strong contender. All taken with Nikon 50mm 1.4 on 4/19/25.

Nikon F2

Insane Luck

It was 2017, and I was at a trade show somewhere in the Pacific Northwest—probably Seattle. I used to attend all these trade shows for work, and we would set up the booth ahead of the event. Well, I was carrying my own film camera around on a strap when one of the union workers stopped me. It turned out he had also once been big into film photography, and we had one of those excellent chats about days gone by. He mentioned he had an F2 that he no longer shot, and I told him that if he wanted, I could give it a new home.

We settled on $150 for the body and three lenses, and he left on his lunch break to go get it. Frankly, this guy was a rough-and-tumble old-timer, and I was expecting a camera that had been through the wringer and back. But when he returned, he was carrying a gorgeous leather camera bag, and inside was the most pristine Nikon I had ever seen. The camera had clearly spent its whole life in one of those leather camera condoms, and it didn’t even have any brassing or scuffs on the paint.

And perhaps even better than being mint—it was all black. I adore the all-black Nikons. One of these days, I’ll open up some space in my budget and buy an FE2 and F3 in all black, but until then, I’ve got this absolute beauty.

History

Honestly, this is an extremely famous camera, and I’m not as excited to do a big write-up on it. Let me summarize by saying that the Nikon F2 was an iconic professional camera with amazing glass and an unbelievably dedicated following. I highly recommend reading Mike Eckman’s post on the camera. He goes into incredible detail on why the camera was such a success, and it’s well worth the read.

If you’re interested in a video overview of the entire Nikon lineup, Tech Heritage has some great videos:

Comparisons

I do, however, want to spend a little bit of time on some comparisons.

The Nikon F2 is the successor to the F and the professional counterpart to the FM2. If you’re in the market for a mechanical Nikon film camera, it’s very likely that the FM2 and F2 are at the top of your list. Let me start by saying that compared to the FM2, the F2 is a larger and heavier camera in every dimension. However, all of its tiny details are also more professional and refined.

In the next few sections, I’ll go over some of the key differences between the two cameras.

Light Meter / Viewfinder

- can be viewed from the top at waist level

- has a needle instead of LEDs

- viewfinder is interchangeable

- HUD: Instead of having the shutter speed, light meter reading, and aperture scattered across the viewfinder, the F2 consolidates all the information into the bottom right of the frame. Additionally, while the FM2’s shutter speed reading can be hard to see if you’re pointing the camera at a dark backdrop, the F2 uses ambient light from the top, making it consistently more viewable. As a side effect of this design, you can meter from the top of the camera without needing to look through the viewfinder.

Shutter

- Self-timer: Lets you set specific times (2–10 seconds) and has a reset button if you decide not to use the timer.

- Shutter lock: adds a second shutter lock as a rotating dial around the shutter

- Mirror lockup: adds this feature as a twisting lever on the aperture preview button

- T mode: adds a T mode to the shutter speed dial, which holds down the shutter button after it is pressed and can be used in conjunction with bulb mode.

- Downsides: The F2 has a maximum shutter speed of 1/2000 instead of the FM2’s 1/4000, but the slow-speed range is significantly improved.

Controls

- Film rewind: adds knurling to the film rewind knob

- Aperture preview: replaces the FM2’s plastic lever with a fancy black and chrome button that matches the lens release

- ISO selection: goes slightly lower than the FM2, down to 6 instead of 12

Lenses

Nikon has one of the larger flange distances of any major SLR manufacturer, which means that adapting other manufacturers’ lenses to a Nikon body is difficult. But thankfully, Nikon is famous for having an incredible selection of excellent glass.

I personally have rather too many Nikon lenses, and since I haven’t specifically mentioned them in my other camera write-ups, I’ll list them here:

- Rokinon 14mm f/2.8

- 24mm f/2.8, non-AI (converted), 500113

- 28mm f/2.8, AI-S Series E, 2025368

- 35mm f/2, non-AI, 884667

- 50mm f/1.8 AI-S Series E, 3291471

- 50mm f/1.4, non-AI, 321577 (1962–1967)

- 50mm f/1.4, AI-S, 5220802

- 55mm f/3.5, non-AI (converted), 743637

- 60mm f/2.8D, macro

- 85mm f/1.8, non-AI, 430447 (1975–1977)

- 85mm f/1.8D

- 105mm f/2.8D, macro

Of these, the 85mm, 24mm, and 35mm all came bundled with my F2, making it probably one of my best Nikon purchases ever. I’ve also owned and sold another 85, 50, 18-140, and a 28-70. I’ll always mildly regret selling the 28–70mm—it was a great lens—but in truth, it spent most of its time on a digital body anyway.

A standout lens in this lineup that doesn’t get nearly enough press is the 105mm f/2.8D. It’s sharp as a tack and takes beautiful portraits and macro shots. If I ever travel with my camera, this is the first extra lens that I take with me.

Tech Specs

- Dates Manufactured: 1971-1980

- My Date: Nov-Dec 1976, how to date

- Camera Type: SLR

- Format: 35mm

- Primary Lens: 85mm f/1.8, 430447, Mar 1975 - Feb 1977

- Minimum Focusing Distance: ~0.85m

- Shutter Speeds: 10s - 1/2000, B, T

- Light Meter: DP-1 finder 651409

- Country of Origin: Japan

- Weight:

- Body: 850g

- w/ 85mm:** 1281g

- Serial Number: 7704912

Nikon F2 Photo Samples

Voigtländer Prominent

Buying a Beauty

I’m going to be honest with you…I bought this camera mainly because it looks freaking sick.

I was in an antique store in Salt Lake City when I caught a glimpse of its gleaming curves, quirky viewfinder, and recto-circular lens hood peeking at me from underneath the glass. Closer inspection revealed that, far from just being gorgeous, it also sported a lovely 50mm f/1.5 lens. This would have been near the pinnacle of consumer lens technology when this camera was released in the 1950s, essentially meaning I could use this camera with full artistic license—something you rarely get in these old bodies.

I covertly checked the eBay prices, bargained the seller down to $400, and walked out with one of the prettiest and most capable old cameras in my collection. It is in absolutely mint condition and has basically every accessory you could want. Honestly, my copy has the look of something that sat in a display case for the past 75 years. If anyone ever did use this camera, they kept it wrapped in velvet the entire time.

Historical Context

Voigtländer is an ancient name in optics. Founded in 1756 by the son of a carpenter, they originally made mathematical instruments. Over the next hundred years, they broadened their scope to include not just precision instruments but optics. So in 1839, when the first publicly announced and commercially viable photographic process—the daguerreotype—was released, they were perfectly positioned to capitalize.

You can see their hands all over the early photographic revolution. They collaborated with Joseph Petzval in 1840 to build the first mathematically calculated, precision objective in the history of photography. A revolutionary lens with 22 times the light-gathering ability of Daguerre’s daguerreotype lens, it was important enough to attract the attention of the Austrian military. Also in 1840, they were the first to make all-metal daguerreotype cameras, and they began releasing photographic plate cameras shortly thereafter.

Fast forward to the 1930s, and Voigtländer was still famous for its folding cameras, notably the Bessa medium-format cameras. But by the 1950s, 35mm cameras were beginning to take over the market. So in 1952, Voigtländer released the Prominent, their 35mm rangefinder flagship.

It was their absolute best, top-of-the-line camera, and it was priced to match. Costing $270 by 1954, this would put it at $3,200 in 2025. They were hoping to compete with the best of Leica and Contax, and on paper, they had a great chance. Voigtländer made some of the best lenses of the day, and they released the Prominent with an all-new lens lineup, including their flagship Nokton 50mm f/1.5—the fastest asymmetric double Gauss lens offered by Voigtländer, comparable to Ludwig Bertele’s Ernostar, the Leitz Summilux, and the Zeiss Sonnar.

Many of the Voigtländer’s competitors featured focal plane shutters, which could only flash sync at certain speeds. Meanwhile the Prominent had a Compur leaf shutter, and could sync at any speed. Although it was limited to a top speed of 1/500 instead of say, the 1/1000 of the Leica III, remember that this was a time period in which common film speeds were 25, 50, and 100 ASA, and the flash was an integral part of many photographers’ toolkits.

But despite the great specs and the gorgeous lens lineup, the Prominent was a limited commercial success. It had an unusual focusing knob on top of the camera and a pitifully small viewfinder that could only be used with the 50mm lens. In 1958, they released the Prominent II to address the abysmal viewfinder, but it was too little, too late. By that time, the Leica M series had exploded onto the market, and Nikon was already making the S2 and other competitively priced models.

Just to illustrate the point: when I saw my own Voigtländer Prominent calling my name under the antique store glass, I literally had no idea what it was. Everyone knows about the Leica M3, and most photographers will similarly recognize the Nikon, Canon, and Contax rangefinders of the 1950s. But the Prominent simply didn’t sell well in its day, and it’s been largely forgotten by history.

Shooting Experience

If you ever have a chance to go out and shoot with a Voigtländer Prominent, I think you’ll begin to understand the low sales numbers. Honestly, it’s terrible to use. Despite being volumetrically about the same size as my Nikon FM2, with film loaded, the Voigtländer weighs a whopping 1144g compared to the Nikon’s 820g. The viewfinder is incredibly far to the right in a way that makes it feel like your face is always in conflict with your hand, and good lord—the viewfinder is shockingly tiny. I’d say it’s about the same brightness and size as my 1937 Leica IIIa, but where the Leica has a magnified, high-accuracy second rangefinder window, the Voigtländer has a small, integrated patch in the middle of the tiny viewing window.

The focusing knob on top of the camera is an absolute mind-fuck and is unlike any other camera I own. To be sure, it’s technically possible to get excellent results with it, but it just feels awful to use. Lest you think it can’t be any different from using knob focusing on, say, a Yashica TLR, let me assure you—it’s a far inferior experience. It rotates smoothly, yet it somehow jerks with the inertia of the lens, always straining your confidence.

With all that out of the way, the build quality is superb. And good god, is the camera gorgeous. With a lens hood mounted and the optional Turnit viewfinder attached, you will have the coolest-looking camera on any photo walk.

Emotionally, I love this camera. Practically, it’s a mess. Despite its wonderful lenses and stunning looks, I rarely take it when I leave the house.

Accessories

I bought mine with just about every accessory under the sun, so let me take a moment to enumerate them here.

Lenses

- Voigtländer Dynaron 100mm f/4.5

- Voigtländer Skoparon 35mm f/3.5

- Voigtländer Nokton 50mm f/1.5, 3837817

There are actually only seven lenses in the entire range, and I have three of them. They all have these awesome names, like the Ultron, the Ultragon, the Dynaron, etc. Reading on Wikipedia about these lenses feels like perusing the fan page of the latest Transformers villains.

“An advanced 7-element 5-group Double Gauss design with an achromatized front group to enhance its performance (especially at wide apertures), the Nokton was reputed to be the best 50mm f/1.5 lens of the immediate post-WWII era, surpassing the 50mm f/1.5 Leitz Summarit (which was based on a prewar Schneider design) and even edging out the renowned 50mm f/1.5 Zeiss Sonnar.” – Jason Schneider

Accessories

- Turnit 3 Viewfinder

- 310/49 lens hood

The Turnit viewfinder is a nifty accessory that mounts on the hot shoe and gives you 35mm, 50mm, and 100mm frame lines. It has this lovely feature where you can flip down the back and rotate it in place to reverse the lenses and give a magnified 100mm view. On the back, there is a little lever that lets you adjust between 1m, 3m, and infinity parallax correction.

Filters

- G2 49s, 302/49, yellow filter

- UV 49s, 317/49

- Focar 1 47mm, 303/47, magnifying snap-on lens

It also came with two additional magnifiers, but I don’t know what lens they go with:

- Focar A 1m, AR 40.5, 343/41

- Focar D 0.15m, AR 40.5, 348/41

Many of the accessories are stamped with “West Germany”.

Tech Specs

- Dates Manufactured: 1952-1958

- Camera Type: Rangefinder

- Format: 35mm

- Primary Lens: Nokton 50mm f/1.5

- Minimum Focusing Distance: ~3ft

- Shutter Speeds: 1s - 1/500, B

- Light Meter: None

- Country of Origin: Germany

- Weight w/ Lens: ~1144g

- Other Resourses:

Voigtländer Prominent Photo Sample

50mm 1.5, tri-max 400, Salt Lake City

50mm 1.5, tri-max 400, Salt Lake City

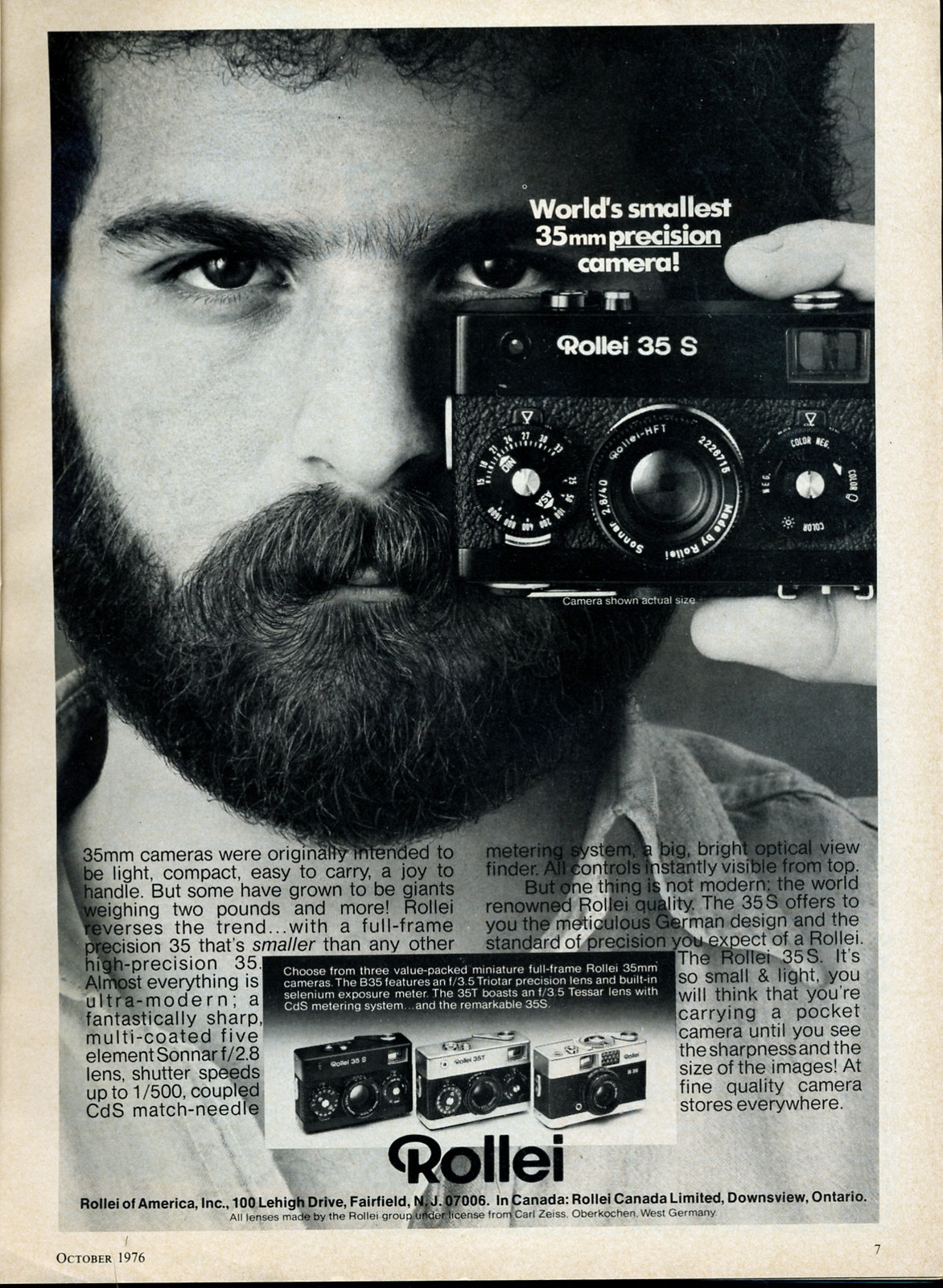

Rollei 35 S

History

In the early 1960s, Heinz Waaske was working for the Wirgin camera company, and he was obsessed with the idea of a full-frame 35mm camera that could fit in your pocket. He spent several years designing one in his free time before finally presenting it to his boss, Heinrich Wirgin, who was reportedly less than thrilled. Irritated that Heinz had used Wirgin’s resources to develop his pet project, their relationship soured, eventually leading Heinz to leave Wirgin.

Unemployed, he demonstrated his prototype to both Leica and Kodak, both of whom rejected it. By 1965, after having his hopes crushed by three separate camera manufacturers, he took a regular job at Rollei, where he kept quiet about his idea.

Rollei itself was founded in 1920 by two former Voigtländer employees, Paul Franke and Reinhold Heidecke. They got their start making stereo cameras like the Heidoscop, and in 1929, they released what is now one of the most famous film cameras in existence, the Rolleiflex. Rollei absolutely dominated the high-quality TLR market, producing a precision, lust-worthy professional camera that spawned countless imitators, such as my Yashica D. However, by the 1960s, the TLR market was shrinking, and Rollei was looking for new ideas.

In 1964, the company hired 38-year-old German physicist Heinrich Peesel as Chairman of the Rollei board of directors. He had produced a detailed report outlining the future path of the company, and his aggressive approach involved moving into new markets, such as slide projectors, a Hasselblad competitor… and 35mm.

In 1965, two months after Heinz was hired, he had a chance meeting with the new Chairman, where he reluctantly showed him his prototype. It was exactly what the Chairman was looking for, and by November 1966, the Rollei 35 was unleashed on the world.

Retailing for a whopping $189.95 ($1,834 in 2025), the Rollei was advertised as the smallest full-frame 35mm camera ever produced. It leveraged Rollei’s design heritage to specifically target the premium market, and it was a resounding success. The camera remained in official production until 1981, with special editions being released sporadically after that, and it is estimated that over 1.5 million Rollei 35s were sold. Although the crown of “smallest 35mm camera” was eventually taken by the partially automatic Minox 35 in 1973, as far as I know, the Rollei 35 remains, to this day, the smallest 35mm camera with full aperture and shutter speed controls.

Its high price raised some eyebrows, but reviews were positive. In his July 1967 review in Camera 35, Jim Hughes reviewed the expensive $189.95 camera, saying that its size and quality invite “amazement, then disbelief, and finally fascination.” He sums up my thoughts perfectly when he says, “when you hold the Rollei 35, you can’t help but know that you’re holding a miniature masterpiece of design.”

My Camera

I got my camera in a bit of a roundabout way. I had the good fortune to buy a high-speed film camera at an estate sale for $6, which I then traded to a friend for a mint-condition Rollei 35 S. Mine is the upgraded S model, manufactured from 1974 to 1980, with the most prominent change being the upgrade from the original 4-element f/3.5 Tessar to my version’s 5-element f/2.8 Sonnar lens. The Sonnar is a truly wonderful little lens, producing sharp and contrasty images with an excellent f/2.8 on such a tiny camera. It is considered one of the best lenses ever put in a compact camera.

My specific camera was produced in 1979, based on having no serial number on the back (1979–) and having the original distance scale numbers (- Dec 1979). If you want to date your own copy, the Rollei Serial Number Database is immensely helpful.

There are quite a few Rollei models—the original 35, the 35 S, the 35 SE, etc.—and serendipitously, mine is the exact model I would have picked if I had had the choice.

Shooting Experience

What’s it like to shoot? Well, to put it simply, I love this little camera.

It’s so disgustingly small that you can casually throw it in a jacket pocket and forget you even have it. It’s so small that they didn’t even bother installing camera strap lugs, instead opting for an elegant wrist strap.

The whole camera is just so elegant and thoughtfully designed. It has a bright and clear viewfinder with infinity and close-focus parallax lines. While holding the camera in both hands, you can look down and see all the settings as you adjust them. First, you note the light reading, then you adjust the shutter speed and aperture with your left and right hands.

As a zone-focus camera, shooting it in a manual version of aperture priority is the most sensible option, and the Rollei engineers have intelligently put a lock on the aperture to prevent unwanted adjustments while leaving the shutter speed dial easier to move. As you look down, you can reference the aperture and then clearly see what range of distances will be in focus. The focusing ring on my example is a bit stiff, but this certainly prevents accidental adjustments.

However, although they have definitely done their best to make zone focusing as easy as possible, it is still zone focusing. Part of the joy of this camera is that they managed to get an f/2.8 lens into such a small package, but the tradeoff is that you will have to be extremely careful if you ever want to use it to its full potential.

If this camera had a rangefinder, you would have a hard time convincing me to shoot with anything else. As it is, I still use it, but I’m rarely willing to take it as my only camera.

Miscellany

As usual, Mike Eckman has an excellent write-up on the Rollei 35, which covers much of what I’ve related here while going into even more detail.

Tech Specs

- Dates Manufactured: 1974-1980

- My Date: 1979, how to date

- Type: 35mm

- Format: 35mm

- Lens: Rollei-HFT Sonnar 2.8/40, 2555662

- Shutter Speeds: 1/2 - 1/500, B

- Minimum Focusing Distance: 0.9m

- Serial number: None

- Country of Origin: Singapore

- Weight: 353g

Rollei 35 S Photo Samples

Rapid Omega 200

This is an astonishingly weird camera. Originally used for aerial photography, it was coopted as a press camera. The film is cycled by pulling a giant lever several inches out of the body, the lens is focused with a rotating knob, and it has delightfully goofy viewfinder attachments.

Rapid Omega 200 Photo Samples

Hasselblad Xpan

Overview

The Hasselblad Xpan is a panoramic rangefinder produced from around 1999-2003. It is insanely expensive (think $4000-$6000), and is the grail camera for many a landscape photographer. Instead of the standard boring 24x36mm shot, it takes gorgeous 24x65 panoramic images on 35mm film. This camera is so iconic that when people modify their medium format cameras to take panoramic shots, they often call them “Xpan mods”.

I only have the opportunity to shoot one because it is on loan from a friend.

Shooting Experience

It feels amazing to shoot. It has literally every creature comfort you could want in a 35mm camera. The viewfinder is bright and clear, the rangefinder is crisp and accurate, it has aperture priority that nails every exposure, the film advances and rewinds automatically…the list goes on.

It’s honestly a little silly how bright and clear the viewfinder is. Interestingly, it leavs a pretty massive amount of space around the frame, which is great for composing shots.

Something I didn’t realize about the camera until I actually had it in my hands is that you don’t have to take panoramic photos with it. You can turn a little knob on the back and switch between 24x36 and 24x65. This is a great feature, as it allows you to take normal shots when you want, and then switch to panoramic when you see a shot that would benefit from it. It also adjusts the photo count and the frame lines in the viewfinder, so you always know what you are shooting.

People talk about how heavy the camera is, but it’s not obtrusive. It’s very densely packed into the body, and it actually weighs less than other brutes such as the F2. Wearing a 24mm/2.8, my F2 comes in at a hefty 1127g, while the Xpan with a 45mm/4 is only 999g.

Actually composing panoramically is much more difficult than I expected. While taking it out, I was constantly seeing wide shots that I thought would be perfect, only to put the camera to my eye and realize that my “wide shot” only filled 3/4 of the frame. This is the sort of camera where I think you could really benefit from spending a week scrolling through other people’s photos to get a feel for what works and what doesn’t.

For a while, I put my phone camera in B&W in full-screen mode (which is still not as wide as the Xpan) and walked around with it glued to my face, just trying to understand what the wide shots would look like.

I sort of thought that the max aperture of f/4 would be a challenge, but for the types of shots I take with this camera, I rarely find myself wanting shallow depth of field.

Tech Specs

- Dates Manufactured: 1999-2003

- Camera Type: Rangefinder

- Format: 35mm, 24x65

- Primary Lens: Hasselblad 4/45, 8YSS21791

- Minimum Focusing Distance:

- Shutter Speeds:

- Light Meter: yes

- Country of Origin: Japan

- Weight w/ Lens: 999g

- Serial Number: 11SV22752

Hasselblad Xpan Photo Samples

Fuji GW690ii

Pictured by itself, you don’t really notice, but the Fuji GW690ii is a massive camera, positively drawfing the normal sized Nikon S2.

Fuji GW690ii Example Photos

Fujica GS645 Pro

Risky Purchase

This is one of my absolute favorite cameras.

The year was 2021. We were all still working from home because of COVID, and anytime I went out for photos, it was with my disgustingly gigantic Pentax 67. At the time, I had it in my mind that I wanted to buy something small and light—something I could take anywhere and still get awesome photos. I was originally looking for Rollei 35-sized rangefinders, but nothing caught my eye until I finally hit the jackpot: folders.

I’ve always been a sucker for unique cameras, and nothing flexes your photography creds quite like a camera with bellows. I quickly honed in on the Fujica GS645 Pro, a 6x4.5 medium format folder with a light meter, rangefinder, and a 75mm f/3.4 lens. It was the perfect combination of modern conveniences and old-timey charm, and I was in love.

Except this was in the middle of COVID, everyone wanted film cameras for some reason, and these Fujis were selling for $700+ in good condition. Since I dreamed of this being my new everyday camera, I was not willing to compromise on quality or condition. Sadly, I was also not willing to spend seven hundred dollars.

Now, I have this friend Greg, who has completely different camera sensibilities from me, and he sent me an eBay listing for a GS645 being sold AS IS for parts. The seller had test photos but claimed it had a broken light meter, broken film advance, and a broken rangefinder—not to mention gross black stuff all over the logo.

I think you literally could not have found a more broken camera. But… it was $200. I talked to Greg, and he was like, “dude has pictures with the camera… good enough for me.” And I was like, Yeah, but he also said, “I have included a few photos I took prior to the rangefinder breaking.” And Greg was like, “eh, probably a screw came out, and he’s too nervous to take the lid off,” before sending me the official GS645 Service Manual. Then Greg sent me a screenshot where he offered $100 and the seller declined.

Well, if there’s anything that motivates me, it’s FOMO and the desire to prove my engineering prowess.

I offered the seller $150, and he accepted.

Repairs

As soon as he accepted my offer, I panicked. I remember texting Greg in a cold sweat, “God, what have I done?” But it was too late.

It came in the mail, and it was, in fact, broken as fuck.

There was mold in the lens, the rangefinder seemed to partially work but slip sometimes, the light meter had some kind of electrical contact issue, and the film advance didn’t work.

Rangefinder

The rangefinder seemed to slip—sometimes working, sometimes not. I opened up the camera and cut a piece of ground glass to fit the back, then tested the focus. (Pro tip: when cutting ground glass, make sure your ruler isn’t too tall for the cutting wheel.) It turned out the focus was perfect at every distance, and the infinity stop was accurate.

I put the camera back together and… the rangefinder worked?

I never did figure out what was wrong with it. Ultimately, it just stopped slipping on its own, and I have no idea what changed.

Light Meter

Sadly, the light meter really was broken, and no amount of opening the camera, anointing it with incense, and sending my prayers to Asano Shūichi seemed to make it any better. The light meter is off by default and is supposed to activate on a half-press of the shutter, but in my camera, you had to press it so far it took the photo, and then the light meter would turn on.

You can enlage the photos to see what I’m talking about, but essentially the lightmeter is supposed to be activated when the shutter pushes down the silver tab so it comes into contact with the black prong. This wasn’t happening early enough in the downward motion of the shutter button, and I looked in vain for a way to adjust the height of the contact point. Finally, I yolo’d it and bent the underside of the shutter so it would push the silver tab down sooner. This worked, but it was a bit of a hack and I would not recommend it.

Film Advance

With the rangefinder and light meter finally fixed, I fully reassembled the camera and was incredibly excited to finally use it when I realized I had forgotten one small detail. The film advance, essentially the only part of the camera that absolutely needs to work, was broken. I had somehow overlooked this fact and was crushed.

Here’s a video of the broken mechanism.

It took me quite some time to figure out, but thankfully, the fix was incredibly simple. I just replaced the wire into the slot it was supposed to be in, and voilà—it worked perfectly.

Bellows

It’s a common saying on the internet that Fujica was ahead of their time… after all, on their top-of-the-line GS645 Pro, they even included a biodegradable bellows.

Like many other disappointed purchasers before me, I was saddened to discover that, despite being basically new by film camera standards, my bellows were beginning to degrade. In fact, they were riddled with little pinhole light leaks.

Now, there are replacement bellows you can buy for $70, but I was loathe to spend seventy extra dollars on a hundred-dollar camera. So I did what any reasonable person would do. I painted the bellows with liquid electrical tape.

Greg likes to say that the best industrial products are the ones that smell the most like they’re going to give you cancer, and I can confirm that liquid electrical tape smells like death. But it worked, and for several years, I had no light leaks.

If you go down this route, I would recommend letting the bellows dry completely and then dusting them in talc before closing them. I didn’t do this, and half of my bellows fused into a solid unit. It still worked for several years, but over time it has developed new leaks, and ultimately, I caved and bought the aftermarket bellows.

Quirks

In addition to being broken, the camera has occasionally done some weird things to me. For example, one time the shutter button stuck, and the camera took a bunch of photos as I cocked the film without me realizing.

Also, it’s pretty easy to accidentally adjust the aperture.

Shooting Experience

My repair saga has perhaps not made the best argument for this camera, but I absolutely adore it. It just takes such excellent photos.

The lens is sharp and contrasty, the 6×4.5 format is the perfect upgrade over 35mm, the light meter is accurate, and the rangefinder is a joy to use. And gosh darn, it’s so small and compact. Seriously, it will fit into the back pocket of a pair of jeans! This is one of those cameras that I would buy again without hesitation if my house burned down.

I see a lot of controversy about this on the internet, but I actually really enjoy the change to a vertical picture-taking format.

If there is one negative, it’s that they have crammed all the controls within 1mm of each other in the exact same spot on the lens, and it’s pretty easy to accidentally adjust the shutter speed or aperture when you meant to do something else.

Tech Specs

- Dates Manufactured: 1983-1985

- Camera Type: Folding Rangefinder

- Format: 120, 6x4.5

- Primary Lens: 70mm f/3.4

- Minimum Focusing Distance:

- Shutter Speeds: 1s - 1/500s, B

- Light Meter: Yes

- Country of Origin: Japan

- Weight w/ Lens: 1m

- Serial Number: ???

- Documentation: Service Manual

Fujica GS645 Pro Photo Samples

Zeiss Super Ikonta 531/2

Background

Back in 2017, I had the good fortune to pick up a mint Zeiss Ikonta 531 B2 for $25 from an antique store in Chicago, and I have been forever impressed with the build quality and hand-feel of the camera. It’s a 6x4.5 model with a 75mm f/4.5 lens and a max shutter speed of 1/300, but sadly, no rangefinder.

Despite the obvious charms of this camera, I’ve always had a difficult time convincing myself to shoot it due to the slow speeds and zone focusing.

However, in the 1930s and ’40s, Zeiss manufactured a whole slew of folders in different configurations. They came in 6×9, 6×4.5, with rangefinders, without rangefinders, f/4.5, f/3.5, etc. So in addition to my rangefinder-less version, they also sold a premium version, the Zeiss Super Ikonta. Surprisingly, these flagship models still fetch a pretty penny today, especially the 6×9 models, as they represent one of the most “affordable” ways to take quality 6×9 photographs.

My Camera

Apparently I hate money, because I shopped around for a minty fresh Super Ikonta before finally settling on what seemed to be an absolutely perfect example for a whopping $340 after taxes and shipping from Japan. In the meantime, I passed up one that was $100 cheaper since it had obvious haze in the lens.

Mine arrived at my door, I opened the box, and it was gorgeous. The whole camera looked like it was made yesterday, instead of literally before my grandma was born.

Except for one teensy-tiny, itty-bitty little problem. The lens had haze.

For those of you in the know, you may have been scratching your head this whole time, because an old uncoated lens like this with haze is a trivial fix. I, too, know this—because I have literally repaired the haze in several lenses before.

So why did I spend one hundred extra dollars for a lens with no haze only to end up with a lens that has haze?

God only knows.

Haze